March 2022

*Edited newsletter with some passed events removed

Dear friends, family, and constituents,

In this week's newsletter and the ones that will follow, I will share the history, ideas, and strategies that were discussed at the Black New Deal Symposium. This event was held on February 26th and kicked off a phase of legislative research and development on how we can address the harms committed to Black Oaklanders after decades of systemic racism present in public policy and programs.

The presentations were full of important contextual information and the discussions were rich with reflection, so I will share all of this over a series of newsletters beginning with this one. Below are some of the key ideas and thoughts presented in the first two sessions.

You can find all the recordings of the presentations on my YouTube page. This Thursday I will have a special guest on my Thursday LIVE, Fmr. Councilmember Robin Rue Simmons who spearheaded a reparations legislative framework in Evanston, Illinois. Please see streaming info below on item 3 in this newsletter.

In service and solidarity,

Carroll Fife

Items in This Newsletter

Professor Nikki Jones Presents on Public Safety at The Black New Deal Symposium

Professor Brandi Summers and Alan Dones Present on Housing at The Black New Deal Symposium

Community Foods Townhall - March 3rd

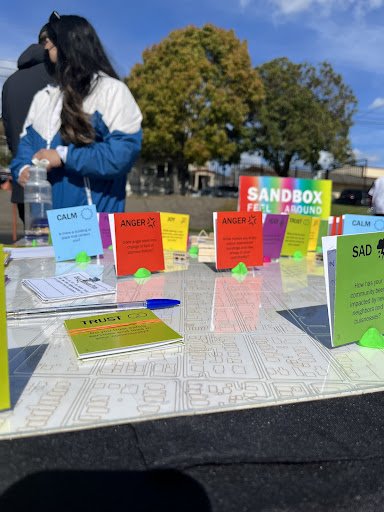

In Community - Images From The Week

The Black New Deal Symposium

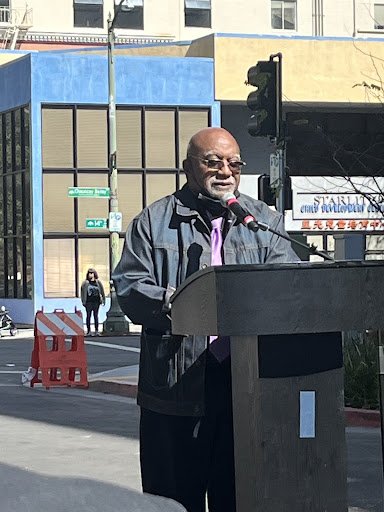

Professor Nikki Jones Presents on Public Safety

Nikki Jones is Professor and H. Michael and Jeanne Williams Department Chair of African American Studies department at UC-Berkeley. Jones earned her Ph.D. jointly in criminology and sociology from the University of Pennsylvania and is considered a leading academic expert on race and the criminal legal system, policing, and violence. Below is a synthesis of her presentation.

Jones discussed how the framework of abolition democracy provides a broader lens for understanding public safety. When we think about abolition democracy we go back to the work of W.E.B. Dubois, who argued that after the one divine event of emancipation, and the victory of getting the black vote, that there was still a gap. What was really needed after emancipation was a commitment to developing the kinds of social institutions that could provide for a multiracial society, a society not based and rooted in racial domination in white supremacy. These social institutions are yet to be built.

So what does it mean to think about public safety through the lens of abolition democracy?

It looks like all the parts of the Black New Deal. It looks like housing, we are on the precipice of a crisis as rent relief expires while rents continue to go up, who is going to be impacted the most? We should be thinking about this as a part of public safety and we should be thinking about the well-being of those who are likely to be displaced and evicted as an element of public safety. Schooling is also an important element along with the need for a just and fair criminal justice system or criminal legal system.

So how do we get that in Oakland?

A study of mass incarceration through a National Academy of Sciences report that came out in 2014 demonstrated that it is the particular politics of race in the United States and the reactionary crime politics that have helped to drive mass incarceration.

Two years ago, the uprisings against systemic racism and police violence seemed to bring an alignment with people centering themselves with those who are most likely to be targets of police violence. Now we see a reactionary response to the spike that is calling for more law enforcement, calling for the heavy hand of law enforcement, even though we know that erodes the safety and well being of communities. It's quite striking to be in this moment where we are returning to those politics and reactionary responses.

What we ought to be doing, what we NEED to be doing, is investing in the kinds of alternatives that build up the capacity of communities. The mayor said maybe a year or so ago, that there's no other research on the kinds of alternatives that will work outside of law enforcement. Coming from the academy, that's just not true. We do actually know the kinds of things that build up the capacity of individuals, social networks, families and communities and we can think about that at a couple of different levels.

A couple of examples of this:

There's research showing that the greening of lots, the abatement of vacant lots, and investments in commercial corridors contribute to the capacity building of a community. What we need to be attuned to in those efforts is that they don't help to spur gentrification and displacement.

The Anti-Police Terror Project and the Mental Health First program might become models for folks around the country.

Investing in alternative responses to crises, particularly those that involve mental health which we know accounts for a significant number of calls for police involvement. MACRO is an example of investing in the kinds of responses that address crises of public safety without exacerbating those crises, which is often the case when police become involved.

Invest in both practices and certain programs that value black life and value black youth; that want to see young people live, not just stop shooting, which is important, but want to see them live and live free outside of prison. One of the most common approaches to violence prevention is to target the same young people who are most likely to be involved in crime, either as a victim or perpetrator of violence, with resources, love and a reason to stop shooting versus telling them to stop or the heavy hand of law enforcement is going to come down on your head.

Change takes time. It requires not just an individual to do something, it requires a community to walk alongside them. Advanced Peace is one model that came out of the Richmond model.

Create buffers and bridges for young people who are likely to be involved in violence. A buffer involves putting ourselves in between young people and the harm that faces them, instead of pushing them further away because of the behavior that they're involved in. And bridges, we know that there's a bridge set up between the neighborhood and the juvenile justice system, between the school and the juvenile in the criminal justice system, but we need those kinds of bridges to other social institutions and organizations that can help to build up the capacity of young people. This is where the investments in the arts and youth serving organizations in culture in the city is essential.

These are all elements of public safety and it shouldn’t be seen as being anti-police to demand that resources be shifted to those organizations because it’s really about the well-being of young people. These investments ensure public safety in a way that is not driven by a moral panic or by white racial fear.

People want a solution to the problem of crime and violence, but history has shown that an increase in policing is not in fact a solution to the problem of crime and violence. More policing has a very marginal, suppression effect, but it is not a long-term solution to solving the problems of violence, which gets us back to the abolition democracy framework in which The Black New Deal is an extension of and sits within.

The Black New Deal forces us to think about reparations. The Black New Deal addresses when the money comes in, where do the investments go and what kinds of protections have to be in place in order to ensure that those investments can have a positive impact. This work can be seen as well within the California Task Force on Reparations and HR 40, the bill for the Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African-Americans Act. This kind of a framework for addressing a host of issues and a host of problems, including public safety, is exactly the kind of conversation framework we need right now.

Professor Brandi Summers and Alan Dones Present on Housing

Brandi T. Summers, PhD, is assistant professor of Geography at UC Berkeley, and is founding co-director of the Berkeley Lab for Speculative Urbanisms. Her research examines the relationship between and function of race, space, urban infrastructure, and architecture. Alan Dones is a Black Oakland developer born and raised in Oakland. This session shared the conditions that have led in part to the staggering levels of Black displacement and dispossession in Oakland. Below is a synthesis of their two separate presentations, beginning with Brandi Summers.

Oakland’s Wartime Industries and Black Migrants

There was one point when West Oakland housed nearly 80% of Oakland’s Black population and was the heart and the center of Black Oakland. Black, as well as white, migration from the South was accelerated after World War I and II due to the availability of jobs in the wartime industries. West Oakland's ideal location along the Bay lent it to become the center for shipping, shipbuilding, toolmaking, and raw material production. The Bay Area in general became one of the largest and fastest growing urban areas during the World War Two era. The Black population expanded at that time as the demand for workers in the shipyards grew, more than 50,000 Black migrants came to the Bay Area between 1942 - 1945.

This rapid influx of new residents to Oakland meant that there wasn't enough housing for migrants. The housing shortage led to the expansion of homeless, unsheltered families in Oakland streets. Despite shipyard workers earning decent wages, they couldn't get adequate housing, which is not unlike our current crisis that we're experiencing today. Oakland City officials expressed concern over the visibility of what they thought were hideous trailer home camps and shanty towns, they argued that this propagated crime and lower property values.

As a result in 1949, all of West Oakland was officially considered blighted by Oakland City Council. The migration of black southerners emerged as a way to classify black people as refugees and temporary citizens of Oakland. This logic made it easy for the city to make way for demolition via what they called slum clearance. This ended up being the primary method that was used to ensure progress and ultimately lead to what James Baldwin has called Negro removal.

Redevelopment and Demolition of Oakland: Acorn

One example in 1956, the newly formed Oakland Redevelopment Agency announced plans for the Acorn area redevelopment project. They designated about 50 blocks in West Oakland to be demolished and this was the first of five major slum clearance areas in the city at the time. The Acorn plan made no provision for public housing, despite the fact that the overwhelming poor population was occurring in the district at this location. The Acorn project at the time was celebrated by city officials and developers as a way to potentially attract white residents and was historically, one of the nation's first attempts at reverse integration. It didn't work.

Black folks in the Acorn region attempted to stop the demolition of their homes by suing the city on the grounds that black homeowners were losing their properties without having anywhere else to go. Ultimately, they lacked the political power to fight the destruction. Federal courts in San Francisco sided with the redevelopment agency and between April 1962 - May 1965, crews destroyed the majority of the 610 structures that comprise the neighborhood. That land that was laid bare had been home to 4300 residents that ended up being displaced. A significant number of Black families were forced to go to other parts of the city like North Oakland and East Oakland, causing those areas to become increasingly overcrowded. Between 1960-1966, West Oakland lost 25% of its population and overall in Oakland during that time period,11,800 units were destroyed, 67% within the poverty target areas.

A City Intentionally Divided Across Racial Lines

With this dramatic demographic transformation, the real estate industry wanted to keep these folks away from the affluent districts in the city in order to protect their property values. The expansion of the federally subsidized interstate highway system, such as those that choke off West Oakland, decimated Black communities through this era. Since the construction was often routed through Black and lower income neighborhoods, it contributed to blight and installed infrastructural impediments to social and logistical circulation, but it also accelerated the deterioration of formally robust Black commercial and cultural hubs such as Seventh Street. As a result, clear racial boundaries were starting to take hold in the city in order to protect the economic interests of the city.

Oakland as a Colony for the Imperial Suburbs

The development of the suburbs hindered Oakland progress during the same years and remade the form, the economy and the culture of several different metropolitan regions in the country, but specifically in the Bay Area. Federal government and local policies ended up institutionalizing discrimination and difference by giving resources mostly to white homeowners in the suburbs, while taking money from these growing Black cities specifically, like Oakland. Significantly, it has led to the gradual accumulation of wealth that white families were able to accrue more readily than Black families. The federal government, the real estate industry, and also related institutions expressly provided opportunities and capital for white families to have access to immeasurable opportunities while denying Black people from taking any part of it.

Racism Codified

Between 1955 -1966, 163,000 white people left Oakland causing the white population to drop 56% due to multiple incentives that were given, including low housing costs. Government insured mortgages made it cheaper to buy a house in the suburbs than to rent in Oakland. Between 1933 - 1963, the Federal Housing Administration ensured $199 billion worth of mortgages, and half of all suburban homes built in the 1950s and the 1960s across the country had FHA mortgages. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's administration explicitly codified racism into the FHA underwriting manual, which in 1938, said "it is necessary that properties shall continue to be occupied by the same social and racial groups." The federal government supported suburbs that prohibited Black people from buying houses through active policy that precluded folks who were not white from receiving suburban mortgages, and so the FHA also ensured very few loans in actual cities, including Oakland that most black people were confined to.

Restrictive Covenants

To make matters worse, the FHA also recommended that suburbs develop restrictive covenants, which forbade black people and other racialized minorities from buying property. There were restrictive covenants all the way up until 1948, when they were outlawed, but places like San Leandro turned covenants into neighborhood Protective Associations. It wasn't until 1968 that the federal fair housing legislation led to policies that prohibited this kind of activity. At the same time, they still enforced this idea and belief that non-white people lowered property values and posed a larger investment risk than white people. So the impact, of course, was very significant. Less than 1% of new housing that was built in the US between 1935-1952 went to Black and other people of color.

Redlining

Relatedly, city districts, including those in the Bay were classified by the government based on perceived investment risks which is where we hear the term redlining. Neighborhoods that were considered desirable in Oakland and other places were given an A rating and colored green, those in the least desirable areas were given a D rating and coded red. These rankings were determined by building age, the conditions of the building, neighborhoods amenities and infrastructure. However, the most important factor that determined neighborhoods classification was its racial composition. What this meant was that even if you had a small black population area, it would get a D rating and that disqualified the residents in that particular area from government insured loans. This made it harder for developers to get money to build in these red areas, hence the term redlining.

All of these factors and so many more led the Black Panther Party to regularly refer to the unequal growth of the East Bay suburbs in comparison to Oakland, as this imperial state exploiting a colony.

Black-Led Development Today In Oakland

Alan Dones discussed how when Black individuals and communities are able to participate in real estate ownership, whether it's a single family home or a high rise office building, they are able to use that real estate equity to raise capital and truly participate in the economic opportunities that come up in an area.

When Black people are able to not only own real estate, but also lead in the development of real estate, we get to make critical decisions about who we hire to design, who we hire to build, who we hire to work in the facilities that are built there, and the future ownership of the small businesses and the home ownership opportunities we design for.

Right now in Oakland, we're living in an environment where even though people of color constitute a majority of the population and contribute to the tax base, when you look at our skyline, the people that are developing our skyline don't reflect the majority of the population of Oakland. The money that was aggregated to build these high rises were in many regards, in most respects, money that we contributed to and a lot of the skyline is built by institutional capital. You have negative consequences that come out of that lack of ability to participate as developers, as facilitators, as well as owners of property and it impacts our community.

A tool for raising funds for development projects is a new type of tax increment financing called an Enhanced Infrastructure Financing Districts (EIFD). It works by freezing the property tax revenues that flow from a designated project area to the city, county, and other taxing entities at the “base level” in the current year. Additional tax revenue in future years (the “increment”) is diverted into a separate pool of money, which can be used either to pay for improvements directly or to pay back bonds issued against the anticipated tax increment revenue.

3. Community Foods Townhall March 3rd

The zoom recording for the townhall that happened last week is now available to view on my Youtube page.